Webcasts

Company Law Update and Outlook 2025

Learn more

Expert insights by Dr Margaret Cullen, Governance Advisor, Institute of Directors Ireland. This blog has been written exclusively for IoD Ireland members.

Corporate governance, including the role of the board and the internal governance frameworks within organisations, is complex. Well-researched and written corporate governance guidance, such as the UK Corporate Governance Code, sound straight forward in principle, but there are complexities in practice related, among other things, to the execution of governance processes and the human dimension of governance. When assessing board effectiveness, it is important both to distinguish between, and understand the relationship and interdependencies between, board structure, board process and behavioural aspects of boards as well as the barriers to effective decision-making that can ensue.

To be effective, a collection of individuals, led by a board chair, must leverage its collective strength, disseminate information provided by executive management, engage across a range of topics, be cognisant of a range of stakeholders, and lead a governance framework that suits its context. The provision of reporting to the board by executive management (“board information”) is a pivotal governance process to which a board’s effectiveness is highly correlated.

The ‘invisible hand’, a concept introduced by Adam Smith is a metaphor for the way the market spontaneously regulates and transmutes voluntary conduct motivated by individual self-interest into the long term collective best interests of society. Regularly, across industries, the invisible hand is not sufficient to promote and ensure the prosperity and well-being of society, so the State intervenes through regulation. Striking the appropriate balance between the invisible hand and regulation becomes a central policy question. Many industries operate with the added dimension of regulatory overlay. Arguably, understanding the difference between regulatory compliance and governance that is overly regulatory led should be a central focus in the boardroom.

The visible hand of management and the board must be the driving force behind any sustainable business, acting as an adjunct mechanism for regulating the interaction between corporations and society. To be clear, companies must act at all times in compliance with the legal and regulatory responsibilities imposed on them. The governance framework of every organisation should support and provide assurance on compliance with that organisation’s regulatory licence to provide a service. The board and executive management should instil the importance of regulatory compliance in every facet of the business and ensure that the internal governance framework facilitates and tests this compliance. In short, the board should ensure, as with risk management and internal control, that the governance foundations are built and that the board, working in conjunction with executive management, agrees the basis of reporting on all matters of interest to the board, including regulatory compliance matters. The chair of the board, in turn, must allocate the scarce resource of time proportionately across the range of topics, key performance indicators (KPIs), key risk indicators (KRIs), and matters reserved, that require board consideration, discussion and decision. Striking the right balance between looking back at past performance and assurance versus forward at emerging risks and opportunities can be challenging for board chairs.

There are many sources of duties and responsibilities to which companies are subject, the primary but not the exclusive source being company legislation. Companies will also have duties and responsibilities related to employment law, data protection law, health and safety law, to name just a few. As noted earlier, companies in certain sectors such as pharmaceuticals, telecommunications, financial services, and the airline industry, can only provide a product or service at the behest of a regulatory licence and must operate and be accountable within a highly regulated environment. While reiterating the point made earlier on the importance of regulatory compliance, all boards should reflect on the rhythm in the boardroom vis-à-vis ensuring the framework for compliance exists and getting assurance on its effectiveness versus allowing the regulatory agenda to consume board discussion and time.

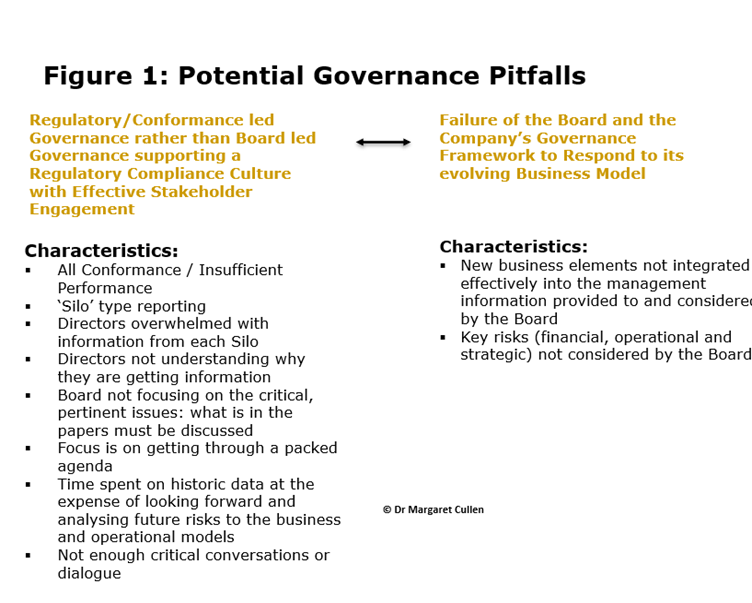

In highly regulated sectors, there is a risk that the information provided to the board and, indeed, the discussion in the boardroom is disproportionality skewed towards regulatory matters and past events, crowding out strategic, forward-looking discussions and debate. Anyone who has ever been in my corporate governance class will know that I am an advocate for regulatory compliance but not regulatory led governance. What we want is board led governance supporting a regulatory compliant culture with effective stakeholder engagement.

Figure 1 below presents the characteristics that might epitomise an overly regulatory led boardroom. Poor standards in reporting to the board can encourage a regulatory led approach. A director mindset that looks only through a regulatory compliance lens can exacerbate this approach.

Through my cross-sectoral discussions with board members, the managerial and detailed nature of information flowing to the board is a constant bug bear with directors, often inhibiting the ability of the board to optimise its performance. Management can often feel pressured to provide the board with a level of granular detail that they do not need, particularly where a regulator has ‘indicated’ its expectations in this regard. This approach creates risk for the board in executing its responsibilities.

At a very basic level, if everything is important how does the chair prioritise discussion? If the board is ploughing through pages of managerial information, is there a danger that the critical issue will be missed? Is the benefit of both delegated authority (and the system of governance put in place to support and create accountability around it) being eroded? Are we blurring the lines between being an executive and being a non-executive director? We must not ignore our cognitive limitations either. Psychologists and behavioural economists have identified many cognitive biases that impair our ability to objectively evaluate information, form sound judgements, and make effective decisions (Beshears and Gino, 2016). It is critical to the effective operation of the board, therefore, that a proportionate, context driven basis is created for reporting to the board.

Executive management have an important role in contributing to the effectiveness of the board and board committees (and de facto the company) through the provision of information to the board and the standard of board papers requiring discussion, debate and decision by the board. Independent non-executive directors (INEDs) have an information asymmetry opportunity and challenge:

The Opportunity: information asymmetry supports the very objectivity and independence they bring to the boardroom.

On this basis, board papers should deliver the following:

It is so important that management work with the board (and its committees) to create the basis, format and frequency of reporting to the board (and/or its committees) across all lines of business and functions:

So, the questions for the board are:

The key question for executive management is:

References:

1. Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, 1776 and The Theory of Moral Sentiments, 1759

2. Beshears and Gino, HBR, 2016, Common Biases that Affect Decision-Making